Scaling in East Africa: Has Uber Peaked in Kenya? – Part 1

This is a guest post from Latiff Cherono. Latiff is a Manufacturing Process Engineer – he helps businesses improve and optimize their processes. Read his first post on this blog, about why your Uber driver may want to take the longer route, and follow him on Twitter—> @LatiffCherono

Introduction

It has been just over two years since the global ride sharing giant Uber, launched in Nairobi, Kenya. Since then Uber Kenya faced numerous local business challenges from initially not being compatible with mobile money, (in a country with over two thirds mobile money penetration usage) to battling with local driver-partners. None of these problems, however serious they may be, are as grave as what Uber may already be facing as they try to scale in Sub Saharan Africa.

In June 2016 Uber drastically reduced their ride fares in a bid to entice more Nairobians to use their platform frequently. While this move was popular with riders, it had an opposite effect on the Uber Driver-Partners which resulted in their striking in August 2016. In another bid to accommodate the price-sensitive Kenyan market, Uber launched their upfront fares in February 2017. Upfront fares provide the rider a guaranteed fare at the time of requesting, regardless of change of traffic conditions during the journey. This change resulted in the most recent driver-partner strike that ironically caused damage some driver-partners vehicles.

To accommodate the driver demands, Uber acquiesced and raised the ride fares again by 20%. This yo-yoing of fares is an indication that Uber has yet to find the right price point that will encourage more people to use their services, as well as keep its driver-partners happy. In addition to these internal business challenges, Uber is facing stiff competition from local and international ride sharing startups (Taxify from Slovenia, Little Cabs from Kenya, Mondo Ride from Saudi Arabia) who are intent on stealing Uber’s sizeable market share.

All these activities have led to the fundamental question that this series of posts will be trying to address.

Has Uber reached its peak in Kenya and more importantly, does it matter?

In a bid to understand the sustainability of the ride sharing business model in Kenya, this article looks at the incentives of the three stakeholders in the ride sharing ecosystem, spread over three articles.:

- Part 1 – The Platform Owner (Uber)

- Part 2 – The Driver-Partner

- Part 3 – The Rider.

After assessing these incentives, we will be able to draw a conclusion that answers the question posed in the title.

Note: As Uber is famously tight lipped with its operational data, I’ve had to draw inferences from my personal conversations with Driver-Partners over the past year and various online sources (cited). I have listed the currencies in Kenya shillings as this will benefit local readers first. International readers can use the conversion factor of KES 100 = US $1.

1. The Platform Owner (Uber)

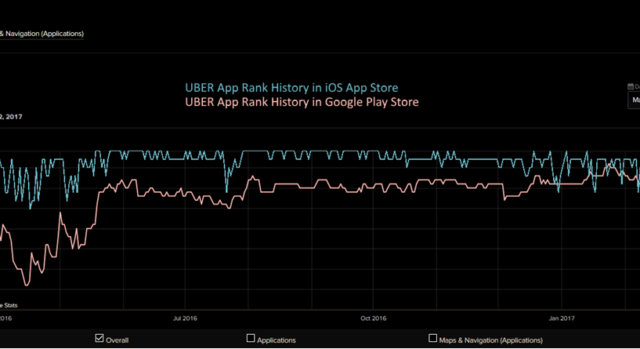

In the Kenyan market, the Uber app maintains a high ranking (via the app analytic service, App Annie).

- Uber is the 2nd most downloaded app on iOS

- Uber is the 9th most downloaded app on the Google Play store.

2: Uber App Store Rating History for past Year.

From the above chart, we can see that the Uber app has been a Top 10 downloaded app on both iOS App Store and Google Play stores for the last year. This popularity validates the following assumption: Anyone in Nairobi who has the means to pay for an Uber ride, has already downloaded the app and tried the service at least once. This means that Uber has already exhausted the base of new customers in Nairobi.

In November 2016 at the 2016 Africa Com conference held in Johannesburg, Uber’s South Africa Senior Operations and Logistics Manager, Timothy Willis, revealed the first data points about Uber’s operations in Kenya. This points are:

- 100,000 plus potential riders open the Uber app every month. A potential rider is someone who has downloaded the Uber app and created an account.

- 1000 plus “economic opportunities” have been created in Kenya since Uber launched. This data point tells us that Uber has signed up approximately 1000 driver-partners. However it does not tell us how many of those drivers are active.

NOTE: It is very important to note that potential rides don’t mean an actual ride as it is a metric of when a registered user opens the Uber App. It is also in Uber’s interest to state the total number of “Economic Opportunities” they have created rather than the true number of Driver-Partners they currently have, as it appears puts Uber in a positive light in having created more “jobs” for the local economy that they are in.

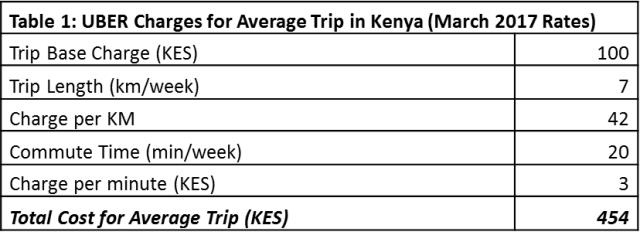

These data points help us estimate the revenue that Uber earns per month in Kenya. To arrive at this estimate, we will make the following assumptions.

- 95% of the 100,000 plus “potential riders” take a ride when their open the Uber app. NOTE: This is a very high percentage, but we will give Uber the benefit of the doubt and make this assumption.

- The average Uber trip per customer is 7 kilometers at 20 minutes per trip.

- There are 1000 Uber Driver-partners on the Uber platform. Of these 1000 drivers, we will assume that only 75% are active throughout the month

From the data tables, above, we can infer the following:

- The Average Daily income per driver is quite low (under KES 2500). From my discussions with various Uber drivers over the past year, I have discovered that the current going rate for leasing a private vehicle to operate as an Uber Cab is KES 2500. The data in Table 2 would mean that Uber is NOT a feasible business for a driver partner as our calculated daily income for the driver is below the standard rental rate for a vehicle. Thus, either the cost of our average trip is too low, or more likely, the number of actual Driver-Partners on the Uber platform in Kenya is much lower than the 75% we assumed. If we change the percentage of online Uber Drive’ partners to 50%, the average daily income per driver jumps to KES 3,178.

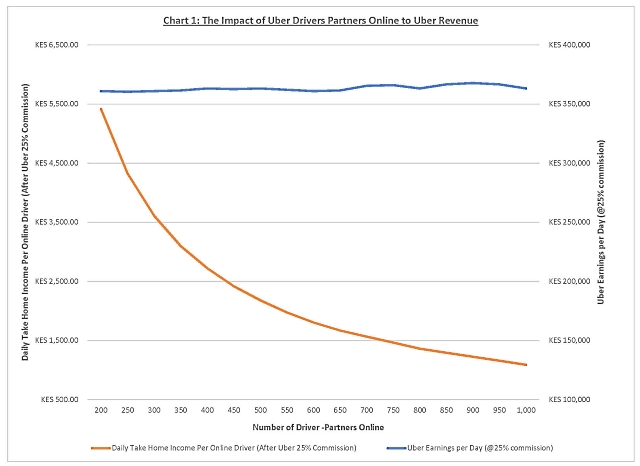

If we assume that the 100,000 potential rides data point is constant monthly, and then plot the number of online drivers versus Uber Revenue, we get the following:

Chart 1 clearly shows that as Uber adds more Drivers-Partners to their platform, the Driver-Partners daily revenue decreases (more drivers competing for the same customer base). Ironically, Uber earnings remain relatively the same. This inference is supported the two trends that we have seen in our market:

- The strikes by Driver-Partners stating that they are not making a sustainable living by being on the Uber platform.

- It is in Uber interest to keep more Driver-Partners on the road as this decreases the wait time (and hence improves customer experience) of their users. As an Uber user, it is apparent to me that number of Drivers-Partners has significantly increased based on the reduced time it takes for me hail an Uber vehicle. Conversely, this increase in Driver-Partners has also reduced the service level of Uber rides (older vehicles and reduced customer service levels). The initial high level of customer service was one of Uber’s key value propositions when they started Kenya operations).

- Uber Price surges have been rare over the last year (excluding surges occurring at specific locations e.g. concerts/sporting events). This means that the current supply of Driver-Partners is more than sufficient to meet the current demand of Riders. NOTE: On the morning of the most recent Uber price hike, Nairobi had an unprecedented city-wide price surge of 1.9X to 1.5X. The surge was caused by a lack of online drivers from those who were striking as well as non-striking drivers who remained offline in fear of their vehicles by the striking drivers.

These three points are good indicators that the customer base for Uber riders has stabilized and is not growing. Thus, to continue scaling, Uber must either add brand new customers to their platform or ensure that existing customers take more rides.

To date, Uber has limited their advertising to physical billboards in Nairobi city as well as an initial social media campaign centering around reduced rates for referrals. Drivers were also given incentives for staying online for longer hours as well achieving certain levels of service delivery. Per my talks with the drivers, these incentives have all been stopped, further indicating that Uber is not seeing continued returns (i.e. continued growth) and thus is minimizing costs. The lack of additional advertising is a telling that Uber has reached the maximum conversion to new customers as well as convincing existing customers to take more rides.

The next post looks at the Partner perspective and the final post, the Uber rider’s.

4 Comments