Scaling in East Africa: Has Uber Peaked in Kenya? – Part 2

This is a guest post from Latiff Cherono. Latiff is a Manufacturing Process Engineer – he helps businesses improve and optimize their processes. Read his first post on this blog, about why your Uber driver may want to take the longer route, and follow him on Twitter—> @LatiffCherono

As Uber approaches its second anniversary in the Kenyan market, there is sufficient reason to believe that Uber may have reached its peak in terms of growth. This series of articles seeks to understand the sustainability of the ride sharing business in Kenya, focusing on the incentives driving the three key stakeholders in the ride sharing ecosystem. Part 1 of this series discussed the data points that showed why Uber (as the platform owner) has plateaued on customer growth. This article evaluates the Partner (Uber likes to call its drivers Partners, because they are not employed drivers, but individuals doing business) incentives to check if they support the thesis of the series. The third article will be looking at the customer perspective.

After assessing these incentives, we will be able to draw a conclusion that answers the question posed in the title.

The Uber Partner

As introduced in the last article, over the last year, there has been at least 2 strikes by Nairobi’s Uber Partners

One of the demands the Partners made during their strikes was that Uber must reduce their commission structure so that they may retain more of the revenue their earned. Thus, it was curious to see that Uber only increased the cost per kilometer in the recent rate hike. I was curious to know:

- How does the current change affect both the Partner and Uber revenues?

- If Uber changed their commission structure, what would the impact be for both parties?

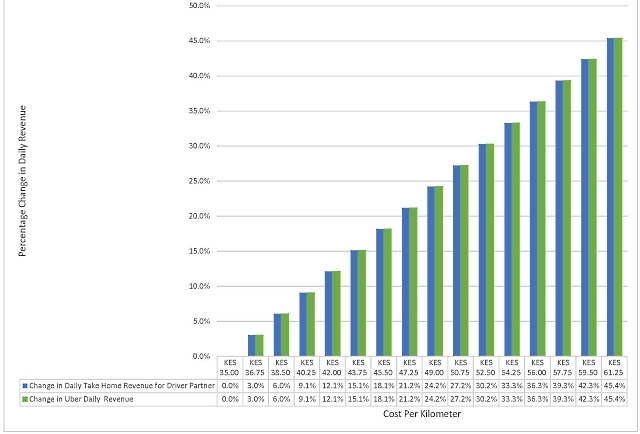

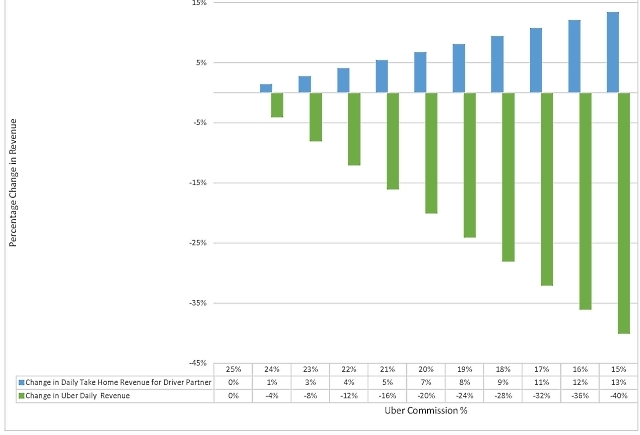

Chart 1: How a rate increase affects Partner revenues

Chart 1 shows us that an increase in the per kilometer rate has the same percentage change in both the Partner’s take home revenue as well as Uber revenues. The increase from 35 KES/KM (0.35 $/KM) to 42 KES/KM (0.42 $/KM) results in a positive change in revenue of 12.1% for both Uber and their Partners Both parties win. We can also assume that Uber settled on the 42 KES/KM as the best compromise between what the typical Kenyan rider will comfortably bear and what will appease the Driver-Partners.

Chart 2, on the other hand shows that if Uber reduced their commission percentage, their Partners would have a slight increase in their take home earnings. However, this would be disastrous for Uber as their revenues would collapse dramatically. This chart shows clearly shows that an on-demand service should only reduce their commission structure as an absolute last resort, or more importantly, the right commission structure should be chosen from the beginning of the service.

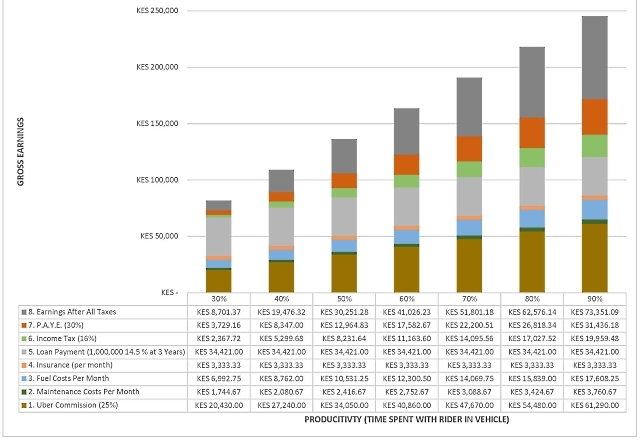

This leaves the Partners in a predicament: how to maximize revenue / operate profitably? Chart 4 plots a Driver-Partner’s gross earnings based on their productivity (productivity = the ratio of time spent with an Uber Rider in the vehicle to the total time working). The more productive a Partner is, the more rides they complete.

We assume that this Partner has a 2009 Toyota Corolla worth KES 1 million ($10,000) that he paying off via a 3 year loan that charges 14.5% in interest. The car’s fuel consumption 20km/l and it is serviced at AutoXpress (a local automotive service chain) every 5,000 and 10,000km. We use the statistics from Part 1 to graph this:

- Average trip length and cost – 7km, 20 minutes, KES 454 ($4.54).

- 100,000 rides per month

- 1000 Kenyan Driver-Partners on the Uber Platform

Chart 3: Impact of Partner productivity on revenues

Chart 3 clearly shows that the best way for Partners to increase their revenues is for Uber to increase the number of rides on their platform. Chart 4 shows that as a Partner improves their productivity, the percentage of remittance to Uber remains the same. and more importantly,the impact of operational expenses on profitability reduces.

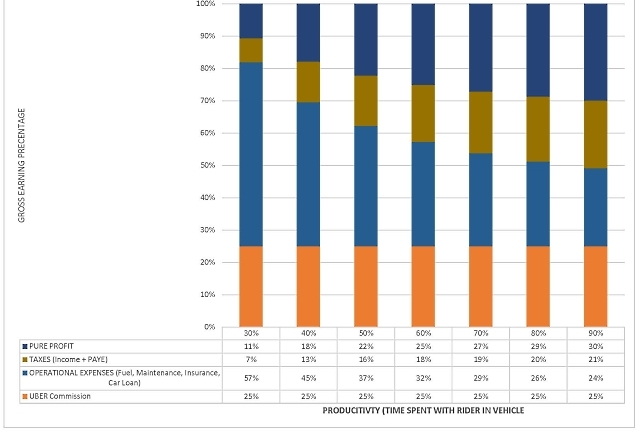

Chart 4: Distribution of Uber Partner Gross Revenue as Productivity Improves

This leads us to the conclusion that a rate increase or a decrease in Uber commissions is not what has the most impact on Partner profitability, but an increase in the number of rides.

From conversations with local Partners, it is apparent that they have had to increase their working times to get more rides. A recent such driver, told me that they are working between 12-14 hours a day during the week and up to 20 hours on the weekend (Saturday through Sunday) to maximize revenue. “Even our children are forgetting our faces”.

Finally, because the Partners are considered contractors and not employees, they don’t get the traditional employee benefits (health insurance, pensions etc.) and must cover these costs themselves. To manage this, many drivers have signed up with competing ride sharing platforms in order to find which service maximizes their returns. This means that the average ride sharing driver is doing a lot more hours than what a single platform is tracking.

If more rides benefit both Uber (the Platform Owner) and their Driver- Partners, then why is Uber having difficulty scaling in Kenya?

The answer lays with the last stakeholder in the Uber equation: the Uber Rider, in the final post of the series.

2 Comments